|

Above: when the comics scene exploded with The Yellow Kid, he appeared everywhere, even on stationary.

This article is a research paper writtten by my friend Tim Palmer, who is a drama major at Agustana College in Rock Island. I've always been impressed with his writing skills, and in this article he turns to some of my favorite comic strips. Pictures tell stories. They always have and they always will. That is why the comic strip will never die. It has become a part of the American way of life. Dad sits in his arm chair reading the news and on the floor, with their elbows propped up, chins resting in their hands, feet swaying back and forth in the air, are the kids, looking with wonder and amazement at the funny pages. This may sound like a scene out of the 40s or 50s, but even 5 decades later you can still find this picture in many American homes on a Sunday afternoon. Just as the comic strip has survived all these years, it has also run the gamut of relevancy in everything from comedy and satire to serious social issues such as war, along the way picking up all thats in between. The comic strip has had an influence on society ever since it was introduced to the American public and will continue to as long as humor, social turmoil, and a love for art exist.

The 1890s marked the beginning of the comic strip with Hogans Alley, created by Richard Outcault. Illustrated newspapers such as Gleason's, Leslie's, and Harper's had existed since the 1850s and were even quite popular, yet they did not see widespread success due to the trouble and expenses that they garnered because of the lack of technology at the time (O Sullivan 10). But on February 16, 1896, America took notice of the comic strip medium, due to the creation of Hogan's Alleys most prominent character, Yellow Kid. The character had appeared in earlier Hogan's Alley strips and was quickly noticed as an integral part of the strip.

Yet when Charles Saalburgh, foreman of the color room at the New York World, decided to test his tallow drying yellow on the then unnamed white nightgown clad character, an unprecedented attention and interest was directed towards the strip that featured the Yellow Kid (Becker 10). He stood out starkly amidst whatever commotion was taking place in the surrounding of Hogan's Alley, usually with some kind of explanation or comment of the scene emblazoned on his yellow nightgown (Becker 11).

The Yellow kid was an independent ragamuffin, and to the immigrants attempting to settle into the American life, he was comfortingly familiar. The background that he deciphered related the crowded tenements and ethnic neighborhoods of the early 20th century New York in which they were trying to survive (O Sullivan 15). Though its scenes were familiar with struggling immigrants, it brought a new point of view and attitude to the average American home. It opened up the world of the slums, displayed ordinary cruelty, slang, and the pride of the poor (Becker 13). Nonetheless, Hogans Alley and its central character, Yellow Kid, were both hugely popular. The strip's urban settings, crowded pictures, expressive style, and slapstick humor reflected a country in transition, a land of developing cities and growing immigrant populations (O Sullivan 15). The bottom line was that Outcault portrayed the world as it was, not as the American family wished it to be (Becker 13).

The creation of the Yellow Kid also brought about the birth of two common characteristics of the comic strip. It was the first time that text was in the drawing, instead of outside of the picture in the form of a caption. The other familiar characteristic established by the Yellow Kid was the creation of a character with a personality striking enough to endear itself to a large number of readers (Waugh 2). This is proved simply by the fact that Yellow Kid became the first merchandised comic character, and he began to show up on buttons, cracker tins, ladies fans, cigarette packs, and oodles of other objects of the age (Harvey 6). The Yellow Kids distribution was fought for tooth and nail by multiple newspapers who wanted to have the most up and coming thing on the market. It is therefore believed that the character coined the term yellow journalism, which pertains to newspapers that feature sensational reporting and eye-catching displays to attract readers (O Sullivan 13).

Winsor McCay took the comic strip to a new level when his Little Nemo in Slumberland appeared in the Yew York Herald on October 15, 1905 (O Sullivan 32). Before this strip, and also during its production, McCay did numerous other well-known strips, particularly Dream of the Rarebit Fiend and Pilgrims Progress. Dream of the Rarebit Fiend was McCay's first foray into the dream world, and it dealt with the subconscious dream life of adults. Each strip told the story of a different person who was disturbed with nightmares due to the consumption of Welsh rarebit earlier in the day (O Sullivan 28). In these stories, an alternate universe dominated by unpredictable rules replaced the dullness and uniformity of everyday life. On the other hand, in McCay's episodic Pilgrim's Progress, the cares of daily life press upon the main character with exaggerated force. Literary themes were now and then incorporated into the Dream of the Rarebit Fiend including Poe's fascination of premature entombment and the familiar concept of a person meeting their double. In addition, Pilgrim's Progress was inspired by John Bunyan's 17th century novel of the same name (O Sullivan 32).

Little Nemo in Slumberland however, was his masterpiece. It marked the first unbroken, continuous comic strip narrative, with an epic story that was told over the course of five years (O Sullivan 14). The central character, modeled after McCay's son Robert, was the young boy Nemo. His name meant no one and he represented the adolescent version of the everyman. McCay's main look for Slumberland was garnered from the art noveau style, which at the time was growing in popularity. Influences from this artistic style could be seen in the inclusion of peacocks, lilies, swans, and water flora, along with some of the character designs and drawing techniques (O Sullivan 32).

McCay also included elements of fairy tales into his strip such as a reigning king, a beautiful princess, and the concept of the quest, both to prove oneself and to benefit the wellbeing of others (O Sullivan 32). Personal experience worked its way into the imagery of Little Nemo in Slumberland. In his earlier years McCay had worked as an artist for the circus and later for a freak show museum. These experiences were the origins of many carnival images in the strip, including clowns, exotic animals, and dancers, not to mention the artistic contortions he created by using the illusion of trick mirrors (O Sullivan 28). McCay filled the strip with visual phenomenon [such as] metamorphosis and action depicted sequentially in virtually slow-motion detail, almost making the panels appear as they were animated as opposed to stoic drawings (Harvey 25).

Through his strip, McCay projected some of the views that would be held by Surrealists in the future, such as unstable appearances, hostile nature, the irrational matching of objects, and the thought of mechanical devices as a threat. In the end, by way of his creators palpable interaction and realistic view of society, Nemo became involved with social problems such as hunger, the decay of urban living conditions, and the inability to bring about social change (O Sullivan 35). This caused the overall theme of the strip, which had been the search for transcendence through fantasy, to turn into an artistic parallel on current events (O Sullivan 14).

Little Nemo in Slumberland was full of fantastic adventures, including travels in time and space [that were] undertaken in a world of grandiose architecture (O Sullivan 32). Winston McCay will always be remembered for his ability to present epic stories and to exquisitely draw everything from characters and animals to backgrounds and buildings with meticulous attention to the tiniest details (Harvey 22). As an artist, he was a master of perspective and had an uncanny architectural savvy. He created an alternate world in which the unexpected [was] ordinary, and from which the mundane [was] excluded (Harvey 22; O Sullivan 35). He produced drawings and fashioned tales that were so involving and fanciful that the people of that time could forget about their troubles for a while; instead embarking on grand and glorious adventures with Little Nemo in Slumberland.

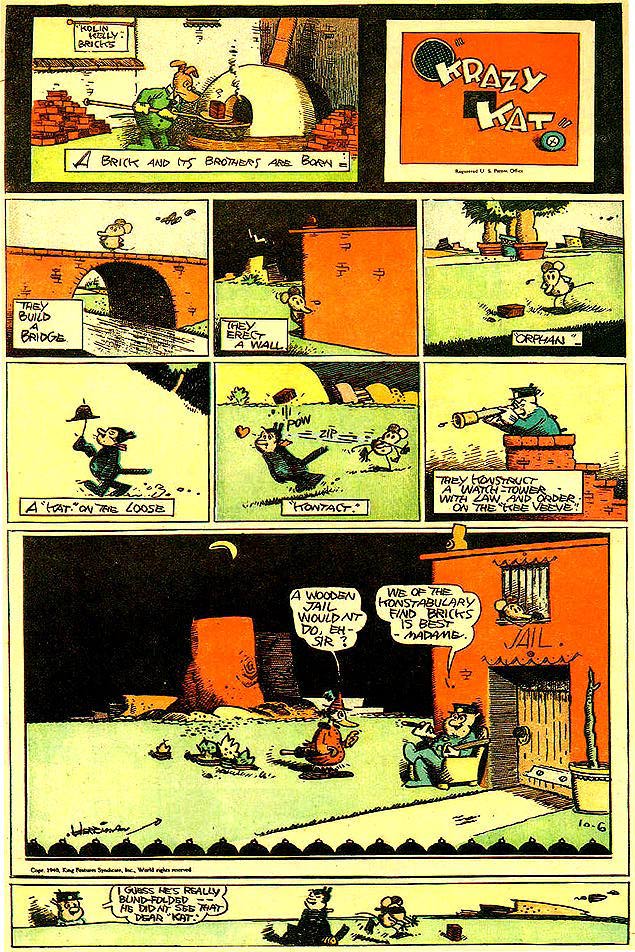

Above: A Krazy Kat sunday page: yet another variation on the theme.

George Herriman, through his remarkable strip Krazy Kat, brought to light the feelings, desires, and questions that were a part of everyday life and humorously explored them through the use of his unique style and dialogue. Krazy Kat, which first appeared on October 28, 1913, is an intellectual comic, full of fantasy and poetry (Harvey 22, 86, & 125). Dealing with themes such as identity, the nature of personal relationships, and the structure of society, Krazy Kat has become one of the most respected comics of all time (O Sullivan 40). The three main characters consist of Krazy Kat, Ignatz Mouse, and Offissa Pupp. The story between these three is unusual in that the cat loves the mouse, yet the mouse despises the cat instead of fearing it, and the dog, instead of chasing the cat, protects it. The true irony lies in the fact that Krazy views the brick that Ignatz throws at him out of anger and annoyance as a missil of love, and that Offissa Pupp only really makes Krazy happy when he fails, as the keeper of the peace, to stop Ignatz's assaults (Harvey 172).

The setting of the strip is that of Arizona's Monument Valley, which heightens the character's relationships, because in this desert, dwarfed by craggy monuments and isolated from the normal bustle of social enterprise, the solitude and insignificance of individual existence becomes a palpable thing (Harvey 178). Though the plot roughly remained the same, the strips format was always changing and testing new ground, exercising to its fullest [Herriman's] increasingly fanciful sense of design (Henry 175). A general theme of the strip was that love always triumphs, in that Krazy is always hit with a brick, which he/she (a gender is never disclosed) views as a sign of affection. A more exact theme is the desire to be love and to be loved, especially since this includes the feelings of Offissa Pupp as well as Krazy Kat's feelings (Harvey 172). Gilbert Seldes states in his book The Seven Lively Arts that Krazy Kat, the daily comic strip of George Herriman is, to me, the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today, and many readers and comic artists would agree (White and Abel 131).

Above: Walt Kelly's cartoon self-portrait

1954 was a tumultuous year for the comic strip. At least it was supposed to be. Dr. Frederic Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent, published that year, blamed comics and their artists for all that was wrong with the world, from murder and rape to juvenile delinquency. In response to this and other related criticism, the Comics Magazine Association of America developed an official code of comic-book self-censorship (O Sullivan 93). Yet this didnt get the comic artists down. They instead stood up, and by way of their artistic talent, made known their constitutional right of free expression (O Sullivan 95). The visual affirmation of the artists rights was led by Walt Kelly, who expressed his disdain for the restrictions through an animal allegory (O Sullivan 95). Senator Joseph McCarthy was conducting his communist witch hunts when the eye of prying investigation fell upon cartoonists. As comic artist Milton Caniff remembers:

Senator Kefauver and a well-meaning committee of Congressmen were holding hearings relating to the evils of the comic books of the day. This was not directed toward newspaper cartoons, but the publicity was touching us and rubbing off. Besides, the comic-book artists were brothers. Kelly organized a counter-move against the negative press all cartoons were getting. In the U.S. Court House on Foley Square in New York a group of cartoonists and illustrators came early and occupied the front seats. As the hearings went on, the Congressmen became aware that we were drawing their portraits. It is hard not to pose when that is going on. Before it ended, the jury was hardly listening to the unhappy book artists. After the session we went from one legislator to another delivering the art. Each Congressman flew home with a half-dozen drawings of himselfand a dim recall of the testimony. (qtd. in O Sullivan 95)

Above: A basic sentiment of Walt Kelly's Pogo.

Walt Kelly's strip Pogo began on October 4, 1948 and it became a platform for the artists battle against Senator Joseph McCarthy. The strip took place in the Okefenokee Swamp, which was a wildlife refuge, and it featured a cast of animals with varying human characteristics. McCarthy appeared in the world of Pogo as Simple J. Malarkey, from May 1, 1953, until October 16, 1954 (O Sullivan 95 & 96). Using Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland as a basis, Kelly created The Pogo Stepmother Goose, which again featured Senator McCarthy, this time as the Red Queen, exclaiming Off with their heads! (O Sullivan 95) The irrationality of the Queens hasty demands paralleled McCarthys unrealistic and unfair trials to seek out communist sentimentalists and expressed the animosity that many Americans had for McCarthy and his overzealous investigations. The U.S. Senate also realized the absurdity of the trials, and McCarthy was censured on December 2, 1954 (O Sullivan 96). Kelly knew the importance of satirizing political turmoil through the comic strip, stating, It should be made clear that to leave out treatment of political themes would be to ignore a mine of comic material so vast that it has at this point merely had its surface sounded with a Geiger counter (O Sullivan 95).

Above: Maus has two stories: The one told by Vladek, and Art's stroy of making a book. The graphic novel keeps cutting between the past and the present.

One of the most important works of the comic genre did not come around until 1986. This was Maus, by Art Spiegelman, and it was groundbreaking. The story is that of Spiegelman's father Vladek, and of his life as a Jew during the Holocaust. Maus helped to establish the 'graphic novel' as a genre and lifted comics as autobiography to new heights of epic expression. Spiegelman deals with very personal and painful memories, such as the deaths of [his] grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins, and brother; his own mental breakdown; [and] his mothers suicide (O Sullivan 136). Maus also deals with the problem of Spiegelman trying to maintain a relationship with his father, who having been through such a traumatic experience has become hollow on the inside. His soul exists, but it is buried under so much suffering that he is nothing more than a frail old man, maddeningly human (O Sullivan 138). He is unable to truly love those that he cares for, creating a strain on his relationship with his son, Art. This relationship, which Spiegelman exposes in Maus, shows the after effects of the Holocaust on the survivor's and their families, and what makes this so meaningful is that we know what is portrayed in Maus is true. It is from the artist's real-life experiences with his father.

In Spiegelman's masterwork, the Jews are mice and the Nazis are cats, which puts the Holocaust in a different light, but it is no less realistic. The characters all have human characteristics, and it takes something that we know well, the cat preying on the mouse, and uses it as a parallel for the most horrendous act in history. There are reasons for the artist's use of animals, as Adam Gopnik states:

Spiegelman's animal heads are, purposefully, much more uniform and mask-like than those of any other cartoonist. His mice, while they have distinct human expressions, all have essentially the same face. As a consequence, they suggest not just the condition of human beings forced to behave like animals, but also our sense that this story is too horrible to be presented unmasked. (qtd. in O Sullivan 138)

The characters do not live in a fanciful realm of beauty and peace, but rather they exist in a violent world in which one species suffers under the oppressive fist of the other and struggles to survive in the face of desolation and fear. They live in a world of sorrow and terror, one that creates monsters and victims, masters and slaves. Through his art and humanistic animals, Spiegelman has helped people to understand the tragedy of the Holocaust and that the pain did not leave with the end of World War Two, but it is instead a lasting sorrow that will stay with humanity until the very end of time. Maus is a testament to that tragedy, but it also shows that the grief can be dealt with, and even overcome, which gives us hope in the human spirit, be it embodied in the form of a man or a mouse.

The comic strip will forever be a part of American society, influencing it through humor, art, and the need for people to see the world and its conflicts in a new and unique way. The Yellow Kid let us know what was going on in the middle class, how life really was, and how the immigrants lived. His yellow nightgown, with the explanation of the melee around him scrawled on the front, first got people to truly see the comic strip as a thing of value.

Winsor McCay raised the comic strip to an art form through his lavish tales of Little Nemo in Slumberland. He put their fears and concerns in strips such as Dream of the Rarebit Fiend and Pilgrim's Progress. He made people look beyond the horizon at what lay ahead, at what the new day may bring. In essence, McCay gave them the ability to dream, and he left them in awe.

George Herriman exposed the struggles of the everyday man to create and maintain relationships through his strip Krazy Kat. He explored the machinations of love and loathing, and with his lyrical and artistic poetry helped a society better understand its emotional undercurrents. Krazy Kat, Ignatz Mouse, and Offissa Pup searched for the meaning behind the way people live their lives and why they do the things they do. Then, by way of Herrimans pen, they shared their findings with a country that wished only to be happy, and to love and be loved in return.

Walt Kelly introduced the people of the 1950s to Pogo, the possum resident of Okefenokee Swamp. His friends consisted of a group of animals that parodied society and allowed people to laugh at the problems around them. He trivialized the world of politics, reminding people that the government was not always right, especially when it came to the Senator Joseph McCarthy and his unconstitutional trials to discover communist sympathizers. He provided people with a different viewpoint to look at the confusing, and sometimes frightening, conditions of their society by bringing political figures into his cartoon world and giving them the characteristics of the animal that best fit their personality and ideals. In this way, Kelly relaxed a generation that was tense and afraid of more things than it needed to be; he gave them the courage to create opinions and to have their own beliefs.

In Maus, Art Spiegelman brought to life the destruction of both the lives and souls of those affected by the Holocaust. He told a story of personal tragedy and triumph, and created one of the best parallels of all time, one that sticks in the reader's mind long after the book closes: he presents this dark period in history through animals, making the Jews mice and the Nazis cats. Maus' simple imagery creates a powerful picture, which reminds us that pictures do tell stories. They tell us stories about our past, our future, our mistakes, and our victories. The comic strip, with all of its varying forms, constantly changing ideas, and unique artists, is one of the largest and most intricate collections of pictures, providing us with many of history's unforgettable stories.

This article contributed by Tim Palmer. |